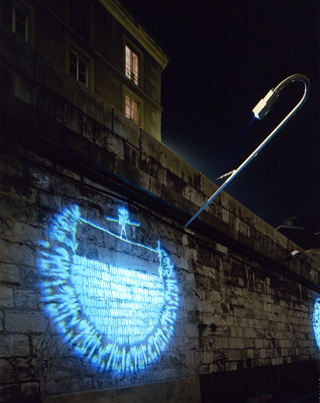

At nightfall, the quays along the Isère River, in the historical heart of Grenoble, open to the world. Fragile and impalpable images, simply made up of shadows and lights, drift along the stream, like a vast frieze underlining the town.

These images have crossed the world to get here. They have been specially created – on a canvas designed by Philippe Mouillon – by artists living around the world, in Egypt or Canada, in Brazil or Japan

Once in Grenoble, the original images are integrated in an experimental technologic prototype designed on Gaz Electricité de Grenoble’s initiative in collaboration with Philips-lighting. They are blown-up on the retaining wall of the quays by a discreet network of optical fibres.

This installation allows the town to live a new and dreamlike life at night. They forgotten quays, exhausted by the intensive traffic, become a place of walk and harmony.

Drawing by Lu Sheng Zhong

Drawing by Rachid Koraichi

Drawing by Rekha Rodwittiya

TEXT BY JACQUES LACARRIÈRE

What is the use of a river? What is the use of a river? The question is hardly ever asked. As for the sky and the earth its existence goes without saying. For a long time rivers have been viewed as a source of drinkable water, a free waterway moving downstream from town to town to reach the sea, as a reservoir of fish one may catch and water fowls one may hunt. Such are the folk tales, the human history of the river at the time of horse-drawn barges and of punts and craft. But rivers have other uses, more for games and less for work, to swim and dive and probe its intimate depths, to sunbathe on their small sand islands, to dream on their banks, imagine their estuaries, the seas into which they flow and the distant Polynesias.

But Heraclites says : “The river is always a Here and a There.” Somewhere else, but also a language, the speech of riverbanks, friendly waters, mud islets, streams, deltas. This language puzzled me, this grammar of swirls and streams either slow or madly swift, waters running from different places.If streams lose their names as soon as they meet a river this doesn’t mean they also lose their distinctive water, I mean the very nature, the density, the singular personality of their water. This is the reason why every river has a history, almost an epic, a long run tale, an aquatic story. When it springs forth it is often but a trickle without a name, without a fate. But as soon as it asserts itself, carries on, digs its way into the incline of the slopes and is framed by the scenery, then it takes on a name, its own name, it can say “I”. But fast enough, while it flows down, others will join him, mingle their waters with his, and the river “I” will lose his identity and say “We” instead. And when this “We” reaches his end and is united with the sea, merges into the vastness of the ocean, he will then lose both his “I” and his “We” and become “All”. Surely there is, in the depths of the Atlantic, rivulets of water still tasting of the Loire, but soon absorbed, drowned into the cosmic taste of the sea, this taste of universal salt.

A river is made up of a thousand different sources and his riches and his reason for being and flowing is the interblending of its waters.

Every river is half breed and interbred. And I no longer want to be told about Roots! I well know the trees. I have grown and matured in their branches, but trees can tell us nothing other than their native soil. They know nothing of the whole world. The whole world can only be taught by rivers on this earth and by migratory birds in the sky.

Rivers are migrating waters, messengers of the universal.

Jacques Lacarrière